African American's Buried at Forest Home Cemetery

It is unknown when the first African American in the Forest Home Cemetery was. With in the last 15 years there is a Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. section available for burials on the western side along First Avenue.

Finally, a headstone for African-American education pioneer

Written by John Rice for the Forest Park Review May 14th, 2013

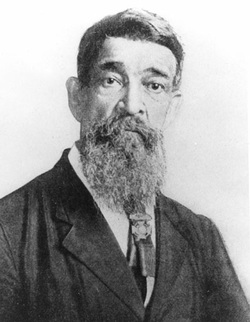

I haven't met Gladys Turner but I'm already a great admirer. Gladys is an 87-year-old social worker from Dayton, Ohio who took it upon herself to honor a pioneering African-American educator.

Joseph Carter Corbin was elected Arkansas State Superintendent of Public Education in 1872. He served as chairman of what became the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville and founded what is now the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff. Following his extraordinary career, Professor Corbin moved to Chicago.

Gladys grew up in Arkansas, where she graduated from Corbin High School and the university at Pine Bluff. This "connection to the professor" inspired Gladys to spend years researching the great man's life. Corbin died in Pine Bluff on Jan. 9, 1911. The maddening mystery was: Where was he interred? "I spent an enormous amount of time trying to find out where he was buried."

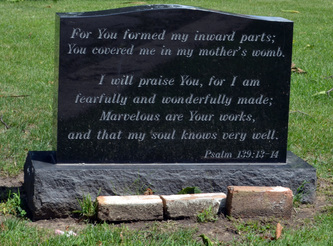

Lo and behold, Professor Corbin, his wife Mary and two sons, John and William, are buried in an unmarked plot at Forest Home Cemetery. After she discovered the graves, Gladys launched the Joseph Carter Corbin Headstone Project. Once the funds were raised, she had the stone made in Dayton. Frank Troost is arranging to have it placed at Forest Home.

Congressman Danny Davis, a 1961 graduate of the university at Pine Bluff, will speak at the ceremony honoring Professor Corbin. It will take place on Memorial Day, at noon, at the Corbin family plot. Back on March 25, the Village Council presented a resolution honoring Professor Corbin. It also praised Gladys for her tireless research.

Corbin was born in Chillocothe, Ohio on March 26, 1833. He was only 17 when he enrolled at Ohio University. He received a bachelor's degree in art and returned to earn masters degrees in 1856 and 1889. Corbin migrated to Little Rock in 1872 and was elected superintendent. He proposed that a college for poor classes be established at Pine Bluff. He advocated for teaching classics to the African-American students but the political establishment insisted they only receive vocational training. Corbin was forced out as superintendent but continued his career as a high school principal. After retiring, he moved with his wife to the South Side of Chicago. On Aug. 3, 1909, he purchased the plot at Forest Home for $125.

Gladys finally solved this mystery when she read an interview with Corbin's daughter conducted shortly after her father's death. She said her parents were buried in Chicago. Gladys discovered his wife, Mary Jean was buried in Forest Home and, sure enough, the professor was right next to her.

Gladys is as feisty as they come. Though she retired from her job as a social worker for the VA, she seems to be in perpetual motion. She's an active member of her socially-progressive church and volunteers at the local historical society. Every time I call her, she's working in her garden. She's taking the Megabus to Chicago for the big day. If you come to the ceremony, you can meet Gladys and hear about the remarkable man described on his headstone as "Father of Higher Education for African-Americans in Arkansas."

Joseph Carter Corbin was elected Arkansas State Superintendent of Public Education in 1872. He served as chairman of what became the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville and founded what is now the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff. Following his extraordinary career, Professor Corbin moved to Chicago.

Gladys grew up in Arkansas, where she graduated from Corbin High School and the university at Pine Bluff. This "connection to the professor" inspired Gladys to spend years researching the great man's life. Corbin died in Pine Bluff on Jan. 9, 1911. The maddening mystery was: Where was he interred? "I spent an enormous amount of time trying to find out where he was buried."

Lo and behold, Professor Corbin, his wife Mary and two sons, John and William, are buried in an unmarked plot at Forest Home Cemetery. After she discovered the graves, Gladys launched the Joseph Carter Corbin Headstone Project. Once the funds were raised, she had the stone made in Dayton. Frank Troost is arranging to have it placed at Forest Home.

Congressman Danny Davis, a 1961 graduate of the university at Pine Bluff, will speak at the ceremony honoring Professor Corbin. It will take place on Memorial Day, at noon, at the Corbin family plot. Back on March 25, the Village Council presented a resolution honoring Professor Corbin. It also praised Gladys for her tireless research.

Corbin was born in Chillocothe, Ohio on March 26, 1833. He was only 17 when he enrolled at Ohio University. He received a bachelor's degree in art and returned to earn masters degrees in 1856 and 1889. Corbin migrated to Little Rock in 1872 and was elected superintendent. He proposed that a college for poor classes be established at Pine Bluff. He advocated for teaching classics to the African-American students but the political establishment insisted they only receive vocational training. Corbin was forced out as superintendent but continued his career as a high school principal. After retiring, he moved with his wife to the South Side of Chicago. On Aug. 3, 1909, he purchased the plot at Forest Home for $125.

Gladys finally solved this mystery when she read an interview with Corbin's daughter conducted shortly after her father's death. She said her parents were buried in Chicago. Gladys discovered his wife, Mary Jean was buried in Forest Home and, sure enough, the professor was right next to her.

Gladys is as feisty as they come. Though she retired from her job as a social worker for the VA, she seems to be in perpetual motion. She's an active member of her socially-progressive church and volunteers at the local historical society. Every time I call her, she's working in her garden. She's taking the Megabus to Chicago for the big day. If you come to the ceremony, you can meet Gladys and hear about the remarkable man described on his headstone as "Father of Higher Education for African-Americans in Arkansas."

Arkansas history honored in Forest Park

Written by John Rice for the Forest Park Review May 28th, 2013

Over 60 people filled the chapel at Forest Home cemetery on Memorial Day for a ceremony honoring Arkansas Reconstruction-era education pioneer Professor Joseph C. Corbin, with many traveling from Arkansas to pay their respects. Corbin died in Chicago in 1911 and was buried in Forest Home.

Joseph Corbin High School graduate Gladys Turner, of Dayton, Ohio acted as mistress of ceremonies welcoming the crowd to a, "historic moment in beautiful Forest Park." Christine Parker, a 1974 graduate of the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff (UAPB) – also founded by Corbin –, gave the invocation: "Thank you Father God for a man who had the vision of giving African-Americans higher education."

In the early reporting about Gladys Turner and her crusade to honor Professor Corbin, there have been a few inaccuracies. Turner is 78, not 87. She was given a ride to Chicago by her neighbor, Vera and did not take the Megabus.

But the most astounding inaccuracy is that there already is an impressive monument engraved with the name Corbin on a family plot that Turner thought was unmarked.

Forest Home's Manager Jim Peters explained that the monument had been placed so long ago; the cemetery had no record of it. When Turner was told there was no grave marker, she was motivated to raise the money for a headstone. She also decided to host a fitting tribute to Professor Corbin on a meaningful holiday. Peters allowed her to hold the ceremony in the cemetery chapel.

Mayor Calderone praised Turner for, "an undertaking that many others would have avoided." He described her passion to bring proper recognition to a great man who had been largely forgotten. He quoted the musician Yanni, who said, "every great thing that has happened to humanity began with a single thought in a person's mind." Addressing Turner, he said, "A great thing has happened here today because of you."

Tony Burroughs, who heads The Center for Black Genealogy, had been instrumental in locating Professor Corbin's grave. "It's extremely important to commemorate the accomplishments of our ancestors," Burroughs said. "Too many of us have unmarked graves." The headstone they were dedicating will be, "a constant reminder of Professor Corbin's accomplishments. Maybe one day a young kid will see the marker and be inspired."

The keynote speaker was Congressman Danny Davis, who acknowledged Mayor Calderone and Commissioner Rory Hoskins as being two of his good friends. The "Proud graduate of Pine Bluff" had enrolled there the same year Turner graduated. Quoting the Bible, he said, "Where there is no vision, the people perish."

"We are here thanks to the vision of Gladys," Davis said.

Davis' parents were sharecroppers and he grew up in a small town in Arkansas, where there was no high school for African Americans. Nevertheless, he and his six siblings all had the opportunity to go to college. Davis came to Pine Bluff, at the age of 16, with twenty dollars in his pocket and a fifty dollar scholarship. The administrator at that time allowed students to enroll on credit. The school was also accommodating about meals. "We got a meal ticket they punched through the same hole every day."

Davis attributed Professor Corbin's success in part to the policies of Reconstruction. "African Americans had the protection of the federal government during Reconstruction and many rose to positions of prominence." He thanked Turner for raising consciousness and awareness of Corbin across the country.

Audience members were invited to speak and Mark Rogovin spoke on behalf of the Historical Society of Forest Park. "When we heard a request for help [from Turner] we never imagined this kind of reception." Rogovin, who led a successful effort to have Paul Robeson honored on a postage stamp, urged Turner to continue her efforts to do the same for Corbin. "Don't give up," he said.

Roland Price, who attended high school in Pine Bluff, is now a Michigan Avenue attorney. He presented a $300 check to Turner. She also received a $500 check from a representative of the Masons. Corbin was very active in that organization and his name is on the cornerstone of the Masonic Temple in Pine Buff.

After the ceremony, the group made their way to the gravesite and placed two floral arrangements on Corbin's grave. One represented the Masons, the other the University of Arkansas. They then repaired to Shanahan's Restaurant for a celebration.

Turner said that after her graduation from Joseph Corbin High School, she went on to Branch Normal College (later UAPB), which was founded by Professor Corbin. "I feel a connection to the professor," Turner said of her education.

Turner used her degree wisely. "I'm proud to be a social worker," she declared. Turner backs up her words by sponsoring a scholarship for students interested in the field. She had a long career as a social worker at the VA hospital in Dayton, Ohio, where she lives today. Turner is also very active in her socially-progressive church, College Hill Community. Turner and the janitor were the first members. They joined during a period of "white flight" in 1965, hoping the church would create a sense of community in their neighborhood.

Apart from attending church functions, Turner volunteers at the Trotwood-Madison Historical Society. She has a deep interest in Black history and is a member of the African-American Genealogy Society. Turner has spent countless hours researching Professor Corbin's life and family history, while searching for his grave. She was inspired in her mission by her late husband Fred. She believes Fred would have been disappointed in her had she given up.

Turner marvels at Corbin's accomplishments. Born in Chillicothe, Ohio in 1833, he rose to become, as his headstone says, "The Father of Higher Education for African-Americans in Arkansas." Despite Corbin's election to Superintendent and his leadership in founding what became the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville, he fell out of favor with the political establishment. He wanted African-American students to receive a liberal arts education. The powers-that-be insisted on agricultural training. Corbin was forced out.

Corbin continued to teach and serve as a principal at high schools in Arkansas until he retired and moved to the Bronzeville neighborhood in Chicago. He purchased the plot at Forest Home for $125. He is buried there with his wife, Mary Jane and his sons, John and Will. Professor Corbin now has two headstones. This should make his admirers in Forest Park and Arkansas doubly proud.

Joseph Corbin High School graduate Gladys Turner, of Dayton, Ohio acted as mistress of ceremonies welcoming the crowd to a, "historic moment in beautiful Forest Park." Christine Parker, a 1974 graduate of the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff (UAPB) – also founded by Corbin –, gave the invocation: "Thank you Father God for a man who had the vision of giving African-Americans higher education."

In the early reporting about Gladys Turner and her crusade to honor Professor Corbin, there have been a few inaccuracies. Turner is 78, not 87. She was given a ride to Chicago by her neighbor, Vera and did not take the Megabus.

But the most astounding inaccuracy is that there already is an impressive monument engraved with the name Corbin on a family plot that Turner thought was unmarked.

Forest Home's Manager Jim Peters explained that the monument had been placed so long ago; the cemetery had no record of it. When Turner was told there was no grave marker, she was motivated to raise the money for a headstone. She also decided to host a fitting tribute to Professor Corbin on a meaningful holiday. Peters allowed her to hold the ceremony in the cemetery chapel.

Mayor Calderone praised Turner for, "an undertaking that many others would have avoided." He described her passion to bring proper recognition to a great man who had been largely forgotten. He quoted the musician Yanni, who said, "every great thing that has happened to humanity began with a single thought in a person's mind." Addressing Turner, he said, "A great thing has happened here today because of you."

Tony Burroughs, who heads The Center for Black Genealogy, had been instrumental in locating Professor Corbin's grave. "It's extremely important to commemorate the accomplishments of our ancestors," Burroughs said. "Too many of us have unmarked graves." The headstone they were dedicating will be, "a constant reminder of Professor Corbin's accomplishments. Maybe one day a young kid will see the marker and be inspired."

The keynote speaker was Congressman Danny Davis, who acknowledged Mayor Calderone and Commissioner Rory Hoskins as being two of his good friends. The "Proud graduate of Pine Bluff" had enrolled there the same year Turner graduated. Quoting the Bible, he said, "Where there is no vision, the people perish."

"We are here thanks to the vision of Gladys," Davis said.

Davis' parents were sharecroppers and he grew up in a small town in Arkansas, where there was no high school for African Americans. Nevertheless, he and his six siblings all had the opportunity to go to college. Davis came to Pine Bluff, at the age of 16, with twenty dollars in his pocket and a fifty dollar scholarship. The administrator at that time allowed students to enroll on credit. The school was also accommodating about meals. "We got a meal ticket they punched through the same hole every day."

Davis attributed Professor Corbin's success in part to the policies of Reconstruction. "African Americans had the protection of the federal government during Reconstruction and many rose to positions of prominence." He thanked Turner for raising consciousness and awareness of Corbin across the country.

Audience members were invited to speak and Mark Rogovin spoke on behalf of the Historical Society of Forest Park. "When we heard a request for help [from Turner] we never imagined this kind of reception." Rogovin, who led a successful effort to have Paul Robeson honored on a postage stamp, urged Turner to continue her efforts to do the same for Corbin. "Don't give up," he said.

Roland Price, who attended high school in Pine Bluff, is now a Michigan Avenue attorney. He presented a $300 check to Turner. She also received a $500 check from a representative of the Masons. Corbin was very active in that organization and his name is on the cornerstone of the Masonic Temple in Pine Buff.

After the ceremony, the group made their way to the gravesite and placed two floral arrangements on Corbin's grave. One represented the Masons, the other the University of Arkansas. They then repaired to Shanahan's Restaurant for a celebration.

Turner said that after her graduation from Joseph Corbin High School, she went on to Branch Normal College (later UAPB), which was founded by Professor Corbin. "I feel a connection to the professor," Turner said of her education.

Turner used her degree wisely. "I'm proud to be a social worker," she declared. Turner backs up her words by sponsoring a scholarship for students interested in the field. She had a long career as a social worker at the VA hospital in Dayton, Ohio, where she lives today. Turner is also very active in her socially-progressive church, College Hill Community. Turner and the janitor were the first members. They joined during a period of "white flight" in 1965, hoping the church would create a sense of community in their neighborhood.

Apart from attending church functions, Turner volunteers at the Trotwood-Madison Historical Society. She has a deep interest in Black history and is a member of the African-American Genealogy Society. Turner has spent countless hours researching Professor Corbin's life and family history, while searching for his grave. She was inspired in her mission by her late husband Fred. She believes Fred would have been disappointed in her had she given up.

Turner marvels at Corbin's accomplishments. Born in Chillicothe, Ohio in 1833, he rose to become, as his headstone says, "The Father of Higher Education for African-Americans in Arkansas." Despite Corbin's election to Superintendent and his leadership in founding what became the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville, he fell out of favor with the political establishment. He wanted African-American students to receive a liberal arts education. The powers-that-be insisted on agricultural training. Corbin was forced out.

Corbin continued to teach and serve as a principal at high schools in Arkansas until he retired and moved to the Bronzeville neighborhood in Chicago. He purchased the plot at Forest Home for $125. He is buried there with his wife, Mary Jane and his sons, John and Will. Professor Corbin now has two headstones. This should make his admirers in Forest Park and Arkansas doubly proud.