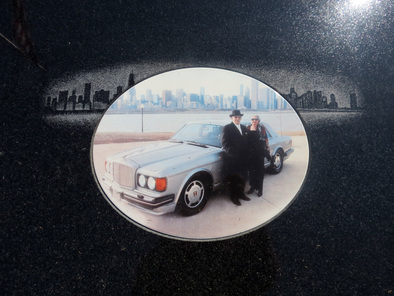

Photo-ceramic

Memorial portraiture is an ancient art, but before photography only the rich could afford to commission sculptures or paintings of themselves. Photography made portraiture available to ordinary people for the first time in history.

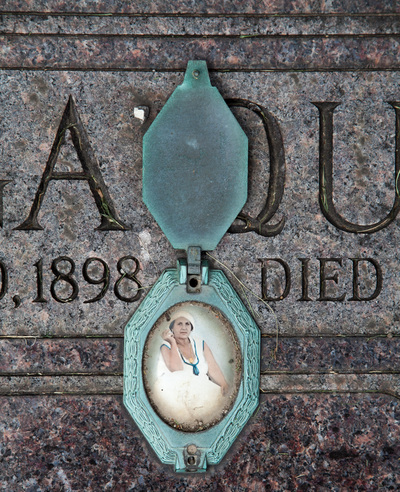

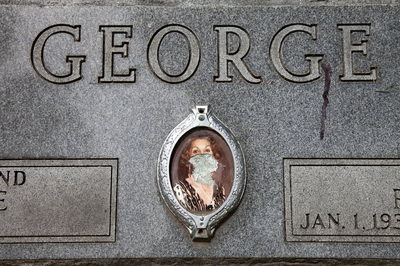

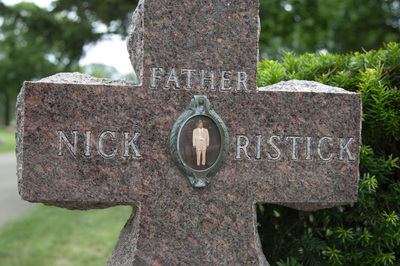

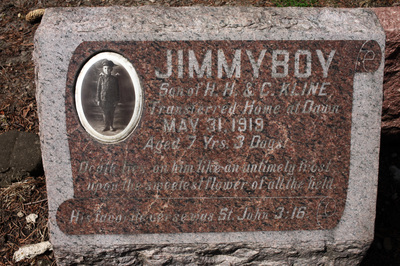

Americans have been attaching photographs to tombstones since the era of the daguerreotype, a process in which light was exposed to silver-coated metallic plates. But enamel photographs proved far more durable. In 1854 two French inventors patented a method for fixing a photographic image on enamel or porcelain by firing it in a kiln. These “enamels” were used for home viewing well into the 20th century, when the more convenient paper photos replaced them. The custom of attaching ceramic photos to tombstones spread throughout Southern and Eastern Europe and Latin America. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Italian and Jewish immigrants brought this practice to the United States. “Ceramic photo portraits . . . represent the first period in the history of gravestone manufacture in the United States when intense personalization became available—and affordable—on a large-scale basis,” says Richard E. Meyer, a professor at Western Oregon State College who has studied American cemeteries for more than 25 years. During the first decade of the 1900s, Sears-Roebuck advertised: “Imperishable Limoges porcelain portraits preserve the features of the deceased . . .” At “$11.20 for a photograph set in marble, $15.75 for one set in granite,” these portraits “competed with the cost of many burial plots.” But the prices were cheap compared to the cost of statuary.

Artisans are still manufacturing enamel photographs, but the process has changed significantly. Early 20th-century craftspeople used chlorides or nitrates of gold, platinum, palladium, and iridium—stable metals that resisted degeneration from heat, sunlight, and other chemicals and gave the photographs a sepia tone. These portraits could last more than 100 years. Contemporary artisans no longer use precious metals, which would make their products prohibitively expensive.

Information from The History Channel Club

Americans have been attaching photographs to tombstones since the era of the daguerreotype, a process in which light was exposed to silver-coated metallic plates. But enamel photographs proved far more durable. In 1854 two French inventors patented a method for fixing a photographic image on enamel or porcelain by firing it in a kiln. These “enamels” were used for home viewing well into the 20th century, when the more convenient paper photos replaced them. The custom of attaching ceramic photos to tombstones spread throughout Southern and Eastern Europe and Latin America. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Italian and Jewish immigrants brought this practice to the United States. “Ceramic photo portraits . . . represent the first period in the history of gravestone manufacture in the United States when intense personalization became available—and affordable—on a large-scale basis,” says Richard E. Meyer, a professor at Western Oregon State College who has studied American cemeteries for more than 25 years. During the first decade of the 1900s, Sears-Roebuck advertised: “Imperishable Limoges porcelain portraits preserve the features of the deceased . . .” At “$11.20 for a photograph set in marble, $15.75 for one set in granite,” these portraits “competed with the cost of many burial plots.” But the prices were cheap compared to the cost of statuary.

Artisans are still manufacturing enamel photographs, but the process has changed significantly. Early 20th-century craftspeople used chlorides or nitrates of gold, platinum, palladium, and iridium—stable metals that resisted degeneration from heat, sunlight, and other chemicals and gave the photographs a sepia tone. These portraits could last more than 100 years. Contemporary artisans no longer use precious metals, which would make their products prohibitively expensive.

Information from The History Channel Club