Iroquois Theater Fire

A terrible blaze occurred at the Iroquois Theater in Chicago on December 30, 1903 as a fire broke out in the crowded theater during a performance of a vaudeville show, starring the popular comedian Eddie Foy. The fire was believed to have been started by faulty wiring leading to a spotlight and claimed the lives of over 600 people, including children, who were packed into the afternoon show for the holidays.

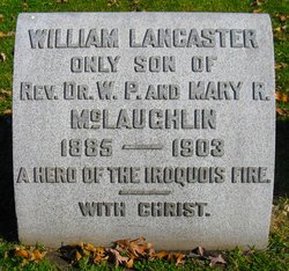

William McLaughlin

Hero of The Iroquois Theater Fire

William McLaughlin and was the nephew of Frank Gunsaulus, also buried at Forest Home Cemetery. He was a college student visiting Chicago and passed by the theater. He rushed into the theater to help rescue people by putting a plank to a neighboring building. He rescued dozens before receiving burns that would then kill him the next day.

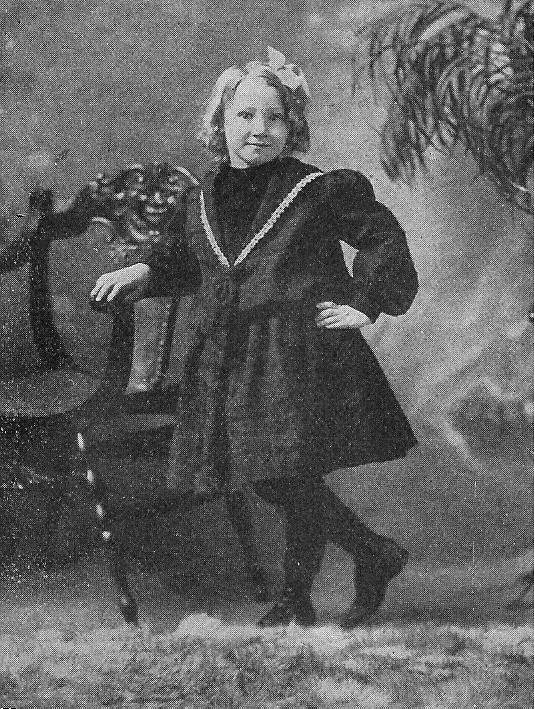

Florence Corrigan

Florence was attending the matinee with a lifelong friend, Miss Viola Delee when she perished in the fire at the Iroquois Theater.

Viola Delee

Viola perished in the fire at the Iroquois Theater. Viola and her friend Miss Florence Corrigan were classmates at St. Xavier's College, where both had graduated in 1901. They were life long friends. On the afternoon of the fire Miss Delee had arranged to meet Florence to attend the matinee. It was thought they had seats on the main floor about eight rows from the front. Their bodies were found lying some distance apart. Both were terribly burned and had it not been for a card in the pocket of Viola's body, Florence would not have been identified. She lived at 7822 Union Avenue, daughter of the late Lieutenant W.J. DeLee of Central Police Detail. Her body was identified by M.J. DeLee, her uncle.

Hero of The Iroquois Theater Fire

William McLaughlin and was the nephew of Frank Gunsaulus, also buried at Forest Home Cemetery. He was a college student visiting Chicago and passed by the theater. He rushed into the theater to help rescue people by putting a plank to a neighboring building. He rescued dozens before receiving burns that would then kill him the next day.

Florence Corrigan

Florence was attending the matinee with a lifelong friend, Miss Viola Delee when she perished in the fire at the Iroquois Theater.

Viola Delee

Viola perished in the fire at the Iroquois Theater. Viola and her friend Miss Florence Corrigan were classmates at St. Xavier's College, where both had graduated in 1901. They were life long friends. On the afternoon of the fire Miss Delee had arranged to meet Florence to attend the matinee. It was thought they had seats on the main floor about eight rows from the front. Their bodies were found lying some distance apart. Both were terribly burned and had it not been for a card in the pocket of Viola's body, Florence would not have been identified. She lived at 7822 Union Avenue, daughter of the late Lieutenant W.J. DeLee of Central Police Detail. Her body was identified by M.J. DeLee, her uncle.

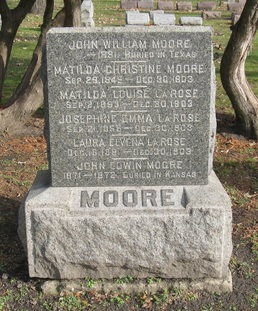

Allen, Amy, Getrude, and Mary W. Badeoch Holst

Mary was the sister of the former Chief of Police Badenoch. The grief at the funeral from the little frame church at Congress street and 42nd avenue was terrible. Inside lay the bodies of Mary A. Holst and her three children; Allan, age 13, Gertrude, age 10 and Amy aged 8 yrs. They perished in the Iroquois Theater disaster. They were in the ill fated second balcony of the theater and met death trying to reach the fire escape. Of the family, only the father and a 6 month old son survived.

Mary was the sister of the former Chief of Police Badenoch. The grief at the funeral from the little frame church at Congress street and 42nd avenue was terrible. Inside lay the bodies of Mary A. Holst and her three children; Allan, age 13, Gertrude, age 10 and Amy aged 8 yrs. They perished in the Iroquois Theater disaster. They were in the ill fated second balcony of the theater and met death trying to reach the fire escape. Of the family, only the father and a 6 month old son survived.

Augusta and Jacob Kochems

Jacob's mother, (listed as Mrs. Frank Kochems on the Iroquois Theater Fire list of victims), perished in the fire along with her son.

Jacob's mother, (listed as Mrs. Frank Kochems on the Iroquois Theater Fire list of victims), perished in the fire along with her son.

Barry and Paul Winder

Paul Age 17, along with brother Barry, 12, died in the Iroquois Theater fire.

Information and photos from Find a Grave

Paul Age 17, along with brother Barry, 12, died in the Iroquois Theater fire.

Information and photos from Find a Grave

The Iroquois Theater fire

A fire during a holiday matinee kills hundreds and leads to tougher safety standards nationwide.

By Bob Secter Tribune staff reporter published in the Chicago Tribune December 30, 1903

A safety standard for theaters and public buildings rises from the ashes of the Iroquois Theater, where more than 600 people were killed.

School was out for Christmas, so the Wednesday matinee performance of "Mr. Blue Beard," a musical starring funnyman Eddie Foy, overflowed with a standing-room audience of nearly 2,000 people, mostly women and children, at the 5-week-old Iroquois Theater.The richly appointed amusement palace on the north side of Randolph Street between State and Dearborn Streets was said to be fireproof. It would prove as unburnable as the Titanic would prove unsinkable nine years later.

In the second act, as the orchestra swung into a dreamy waltz called "Let Us Swear by the Pale Moonlight," an arc light on the left side of the stage sputtered and ignited a strip of paint-saturated muslin on a drape. Unnoticed at first by the audience, the flame ran up the strip and into the fly space above the stage where scenery hung.

Suddenly, blazing fabric rained down on the stage. The singers raced off, one with a costume on fire, and the audience began to bolt. Foy then ran onstage, raised his hands and tried to calm the crowd.

For a moment, the panic eased. But the draft from an open stage door fed the flames. A fireball leaped across the footlights and engulfed a velvet curtain. Stagehands tried to lower the asbestos curtain to keep the blaze from spreading to the seats, but it stuck a few feet above the stage floor. Then part of the stage collapsed, and the lights went out.

That touched off a stampede for the 27 exits, some of which were hidden by drapes; others were locked to foil gate-crashers. Bodies slammed into bodies. Within minutes, tangles of corpses were piled 7 feet high as the living groped for an escape route over the dead, only to succumb themselves to gas, smoke and flames.

By the time firefighters fought their way inside, an eerie silence had fallen over the charred and darkened remains of the theater.

"Is there any living person here?" one fire marshal shouted over and over. "If anyone is alive in here, groan or make a sound." No one did.

Some 575 people died that day, and hundreds were hurt. Another 30 would die from their injuries in the following weeks. The theater's managers and several public officials were indicted in connection with the fire, but none was ever punished.

The tragedy also spurred a drastic toughening of safety standards for theaters and other public buildings, and the rules became a benchmark for the nation. Henceforth, all theater exits had to be clearly marked and the doors rigged so that, even if they could not be pulled open from the outside, they could be pushed open from the inside.

A safety standard for theaters and public buildings rises from the ashes of the Iroquois Theater, where more than 600 people were killed.

School was out for Christmas, so the Wednesday matinee performance of "Mr. Blue Beard," a musical starring funnyman Eddie Foy, overflowed with a standing-room audience of nearly 2,000 people, mostly women and children, at the 5-week-old Iroquois Theater.The richly appointed amusement palace on the north side of Randolph Street between State and Dearborn Streets was said to be fireproof. It would prove as unburnable as the Titanic would prove unsinkable nine years later.

In the second act, as the orchestra swung into a dreamy waltz called "Let Us Swear by the Pale Moonlight," an arc light on the left side of the stage sputtered and ignited a strip of paint-saturated muslin on a drape. Unnoticed at first by the audience, the flame ran up the strip and into the fly space above the stage where scenery hung.

Suddenly, blazing fabric rained down on the stage. The singers raced off, one with a costume on fire, and the audience began to bolt. Foy then ran onstage, raised his hands and tried to calm the crowd.

For a moment, the panic eased. But the draft from an open stage door fed the flames. A fireball leaped across the footlights and engulfed a velvet curtain. Stagehands tried to lower the asbestos curtain to keep the blaze from spreading to the seats, but it stuck a few feet above the stage floor. Then part of the stage collapsed, and the lights went out.

That touched off a stampede for the 27 exits, some of which were hidden by drapes; others were locked to foil gate-crashers. Bodies slammed into bodies. Within minutes, tangles of corpses were piled 7 feet high as the living groped for an escape route over the dead, only to succumb themselves to gas, smoke and flames.

By the time firefighters fought their way inside, an eerie silence had fallen over the charred and darkened remains of the theater.

"Is there any living person here?" one fire marshal shouted over and over. "If anyone is alive in here, groan or make a sound." No one did.

Some 575 people died that day, and hundreds were hurt. Another 30 would die from their injuries in the following weeks. The theater's managers and several public officials were indicted in connection with the fire, but none was ever punished.

The tragedy also spurred a drastic toughening of safety standards for theaters and other public buildings, and the rules became a benchmark for the nation. Henceforth, all theater exits had to be clearly marked and the doors rigged so that, even if they could not be pulled open from the outside, they could be pushed open from the inside.