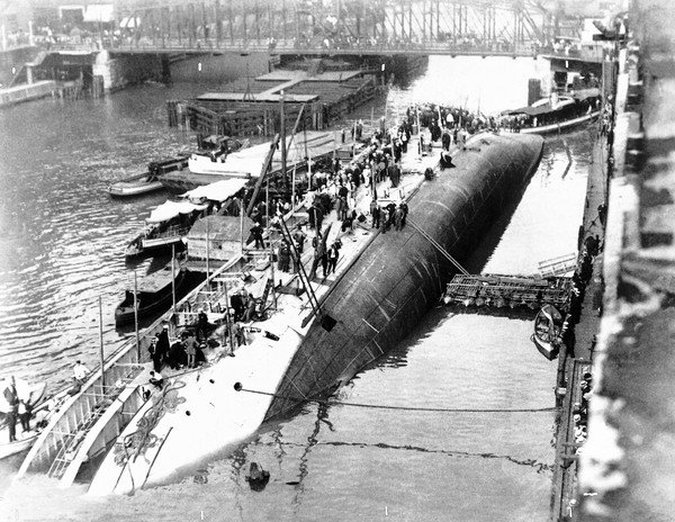

Eastland Ship Disaster

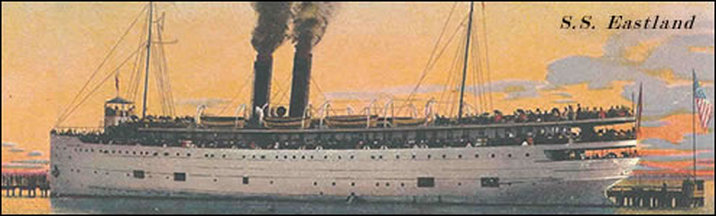

A lake passenger steamer, the S. S. Eastland had been chartered by Chicago's Western Electric Company to transport the company's employees (and their families), to their annual picnic in Michigan City, Indiana. At 7:28 a.m., still moored to her Chicago River dock and with 2,572 people on board, the S. S. Eastland began to list. The steamship managed to briefly right herself before slowly rolling on her side. 844 people died that day in what would turn out to be Chicago's worst disaster ever. An estimated 65 victims are buried in Forest Home Cemetery. Other victims are buried at Concordia Cemetery, Forest Park; Jewish Waldheim, Forest Park; Queen of Heaven, Hillside; Bohemian National Cemetery, Chicago.

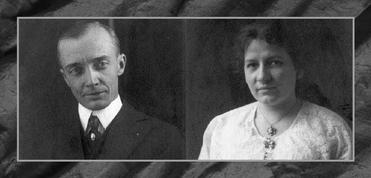

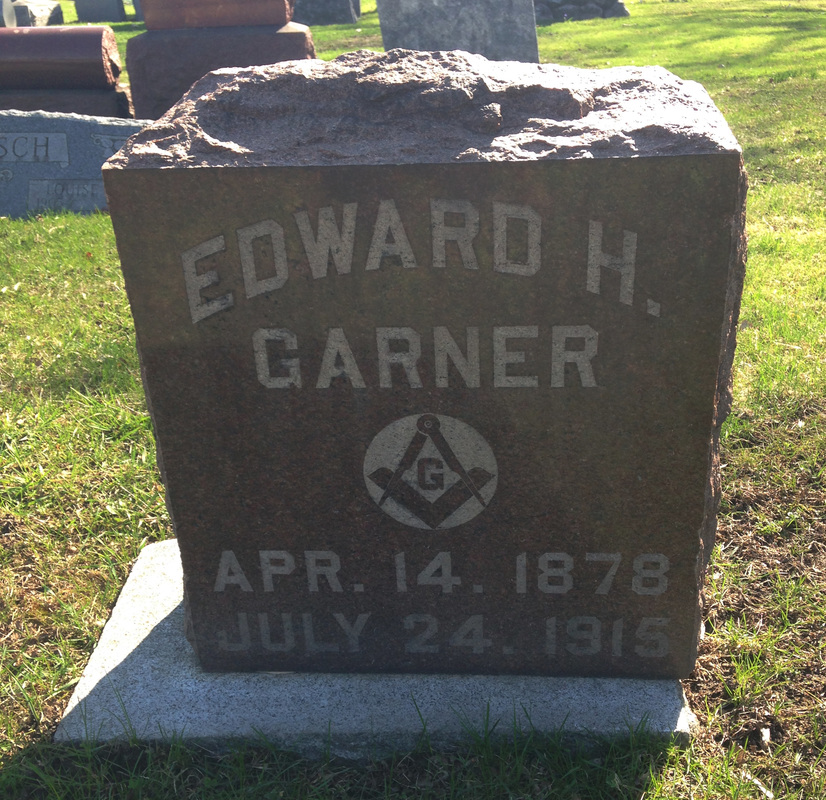

Though they married late in life, especially for the time, they were very much in love. Edward was truly Friederika's one great love. News of Edward's death on the Eastland devastated Friederika. Stricken with grief, Friederika removed all pictures from her home and rarely, if ever, spoke of her husband. Several months after his death when their only child was born, Friederika named their daughter Edros Henrietta Garner after her one true love. Friederika never remarried.

This is the last picture of Edward Henry Garner and his wife Friederika, taken July 11, 1915.

This is the last picture of Edward Henry Garner and his wife Friederika, taken July 11, 1915.

Ada, Clifford, Cora, Hazel, Anna and Edward Hipple

Cora May, age 41, her daughter, Hazel Marie, age 13, her son, Clifford Edward, age 7, her mother, Anna N. Stamm, age 63, and a member of her family, Ada W. Hipple, all perished in the S.S. Eastland Disaster on the Chicago River. Cora May is survived by her husband, John.

Cora May, age 41, her daughter, Hazel Marie, age 13, her son, Clifford Edward, age 7, her mother, Anna N. Stamm, age 63, and a member of her family, Ada W. Hipple, all perished in the S.S. Eastland Disaster on the Chicago River. Cora May is survived by her husband, John.

Photo courtesy of Eastland Disaster Historical Society

Photo courtesy of Eastland Disaster Historical Society

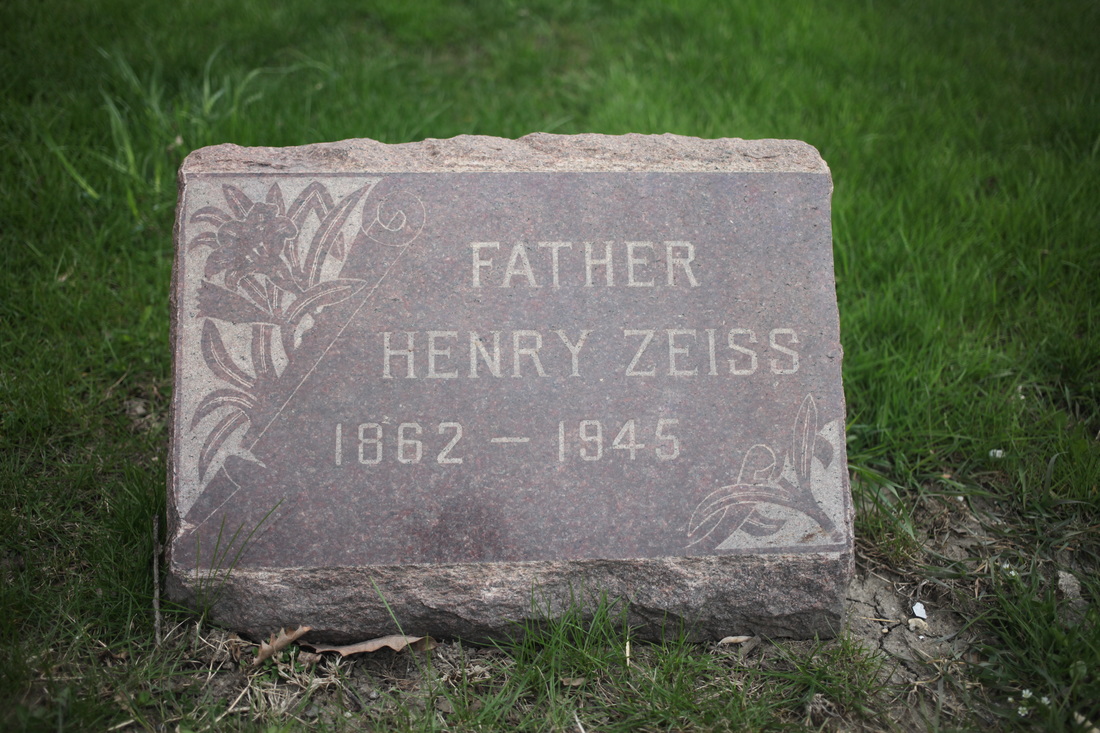

George W. Jost George W. Jost was an employee of the Western Electric Company and worked at the plant in department 2031 for two years. He lived on Komensky Avenue with his parents Henry and Emma, and his two sisters Doris and Evelyn. George cared so deeply for his family -- he had been turning over his entire earnings to his family to help pay for their home.

George left home with a friend early on the morning of July 24, 1915 with plans to enjoy the day at the Western Electric Company excursion and picnic. After he and his friend boarded the S.S. Eastland, George, a violinist, went below deck to listen to the music.

George was sadly trapped below deck when the Eastland capsized and perished that day. His friend survived.

George's father Henry made several trips to the temporary morgue at the Armory building before locating and identifying his 17-year-old son's body.

George left home with a friend early on the morning of July 24, 1915 with plans to enjoy the day at the Western Electric Company excursion and picnic. After he and his friend boarded the S.S. Eastland, George, a violinist, went below deck to listen to the music.

George was sadly trapped below deck when the Eastland capsized and perished that day. His friend survived.

George's father Henry made several trips to the temporary morgue at the Armory building before locating and identifying his 17-year-old son's body.

Margaret Anna Mann

Margaret, age 17, perished in the S.S. Eastland Disaster on the Chicago River. Margaret was employed as a clerk at Western Electric.

Louis Maranz

Louis, age 21, perished in the S.S. Eastland Disaster on the Chicago River. Louis was employed at Western Electric.

Mary Martin

Mary, age 40, perished in the S.S. Eastland Disaster on the Chicago River. Mary is survived by her husband, Louis.

Margaret Olson

Margaret, age 24, perished in the S.S. Eastland Disaster on the Chicago River. Margaret was employed as an inspector at Western Electric.

Joseph J. and Marion Pavletich

Joseph, age 24, and his sister, Marion, age 17, both perished in the S.S. Eastland Disaster on the Chicago River. Joseph was employed as a plumber.

Margaret, age 17, perished in the S.S. Eastland Disaster on the Chicago River. Margaret was employed as a clerk at Western Electric.

Louis Maranz

Louis, age 21, perished in the S.S. Eastland Disaster on the Chicago River. Louis was employed at Western Electric.

Mary Martin

Mary, age 40, perished in the S.S. Eastland Disaster on the Chicago River. Mary is survived by her husband, Louis.

Margaret Olson

Margaret, age 24, perished in the S.S. Eastland Disaster on the Chicago River. Margaret was employed as an inspector at Western Electric.

Joseph J. and Marion Pavletich

Joseph, age 24, and his sister, Marion, age 17, both perished in the S.S. Eastland Disaster on the Chicago River. Joseph was employed as a plumber.

Martha K. Petersen

Martha, age 22, perished in the S.S. Eastland Disaster on the Chicago River. Martha was employed as a tester at Western Electric.

Minnie Metler Rylands

Minnie, age 27, perished in the S.S. Eastland Disaster on the Chicago River. Minnie is survived by her husband, James.

Martha, age 22, perished in the S.S. Eastland Disaster on the Chicago River. Martha was employed as a tester at Western Electric.

Minnie Metler Rylands

Minnie, age 27, perished in the S.S. Eastland Disaster on the Chicago River. Minnie is survived by her husband, James.

Photo courtesy of Eastland Disaster Historical Society

Photo courtesy of Eastland Disaster Historical Society

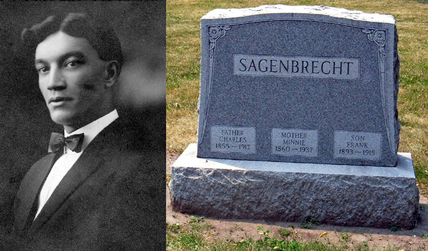

Frank Sagenbrecht

Frank, age 22 perished in the S.S. Eastland Disaster on the Chicago river.Frank Sagenbrecht was one of ten children of Mr. and Mrs. Charles Sagenbrecht. He was educated in the Chicago public schools and worked at Armour & Company. Frank was invited to the picnic by his fiancee, Miss Martha Quwas, who was an employee of Western Electric. Both Frank and Martha perished in the tragedy.

Frank, age 22 perished in the S.S. Eastland Disaster on the Chicago river.Frank Sagenbrecht was one of ten children of Mr. and Mrs. Charles Sagenbrecht. He was educated in the Chicago public schools and worked at Armour & Company. Frank was invited to the picnic by his fiancee, Miss Martha Quwas, who was an employee of Western Electric. Both Frank and Martha perished in the tragedy.

Chicago’s Worst Tragedy Occurred in the Chicago River

Written by The Eastland Fellowship Authority at the Center for History

Drizzling rain did not hamper the spirits of the picnickers boarding the S.S. Eastland heading to Western Electric’s annual picnic in Michigan City, Indiana on July 24, 1915. The Hawthorne Club at the Western Electric plant in Cicero organized the event and sold 7,000 tickets to employees for their family and friends. Everyone anticipated a day filled with games, food, swimming, relaxation, and fun. Parents held their children’s hands as they walked through the crowded decks and looked for a place to sit. For some this would be their first boat ride which raised the expectation of a day to remember. Five boats were chartered but the Eastland, the largest, was the first scheduled to depart at 7:30 a.m. Ticket takers counted 2,500 eager passengers before raising the gangplank and directing people to the other steamers.

The band was playing on a lower deck and guys and gals danced as the boat swayed back and forth. It was a remarkable scene filled with gaiety and anticipation. As the steamer was getting ready to depart, the ship listed to port and then to starboard but seemed to right herself. Passengers were not concerned until she listed to port again and things started to fall. Within two minutes the Eastland was resting on the floor of the Chicago River. Pandemonium broke out – people screaming and jumping into the river, others tightly holding on to their children, and some were climbing over the deck railing to the side of the ship which had risen out of the water. Those below were grabbing onto whatever they could to keep their heads above the water. A few managed to slip out of 18” port-holes resting above the water. Eventually grasps gave way and many were lost in the depths of the ship decks before divers and welders could save them. Bystanders were tossing items into the river hoping these would keep someone afloat. Individuals were diving in the river to rescue as many as possible.

In the end 844 people perished including 22 entire families. Temporary morgues were setup and the task of identifying loved ones was overwhelming. Spouses were lost, children became orphans, and parents cried over the loss of their children. Some families rejoiced in the safe return of loved ones while mourning the loss of other family members. Many families lost their only source of income. The capsizing of the S.S. Eastland marked the greatest loss of life in Chicago or the Great Lakes.

Chicago jumped into action to help from rescue efforts to raising funds. Within two weeks $350,000 was raised for the relief of those families in need. Businesses helped in many ways, for instance Marshall Fields sent blankets to cover the victims and warm those pulled from the river. Storefronts and hotels opened their doors as shelters and medical stations. Phone lines were installed and lists of victims and survivors were complied and forwarded to the switch board operators at the plant in Cicero.

Western Electric provided compensation to the families by establishing two funds. One was to help with the funeral expenses including cemetery plots and even a new suit if necessary. The other provided funds for food and everyday expenditures. The company gave needed medical care and inoculated over 200 people against typhoid, and adopted a policy of favoring victims’ relatives in application for employment.

Czech, Polish, German, Italian, and Swedish immigrants were among the nationalities employed at the Western Electric plant in Cicero. Individual ethnic groups responded and offered assistance. Organizations such as the Masons and Order of the Eastern Star aided with the financial burden of burying the victims as well as supporting and comforting families. An Eastern Star member attended numerous funerals and wrote, “It rained all week at all burials. It seemed as if the heaven was weeping too.”

Newspapers across the country reported on this horrific incident with some sensationalism, such as 1,200 people dead, or 300 still missing. Nonetheless, newspapers were the best source of information and quickly the number of victims was reduced. Everyone wanted to know the cause of the disaster. Fault was wide spread and contributed to improper construction of the steamer, faulty equipment, negligence of the captain and engineer, graft and greed. Naturally, those involved cast the blame on to others. Testimonies were heard and recorded; insurance coverage was certainly not adequate so the families of the victims had to shoulder another burden. The possible causes leading to the S. S. Eastland rolling on its side have been defined yet still disputed. Some like to say she was simply a “cranky ship” and never should have sailed. Testimony proved she sailed for twelve years without incident if the water ballasts contained water. Who was responsible for the water ballasts and keeping the ship even keel is also debated. Trying to find the answer to why the S. S. Eastland capsized was never resolved. Even after almost twenty years of criminal and civil investigation no one was held responsible.

Regardless of the cause, the story of the Eastland Disaster should focus on the people who perished and their families, those who rescued so many survivors, and the businesses and organizations that offered assistance that fateful day. It truly is a story of a community coming together to pay respect to the victims and help the survivors.

The band was playing on a lower deck and guys and gals danced as the boat swayed back and forth. It was a remarkable scene filled with gaiety and anticipation. As the steamer was getting ready to depart, the ship listed to port and then to starboard but seemed to right herself. Passengers were not concerned until she listed to port again and things started to fall. Within two minutes the Eastland was resting on the floor of the Chicago River. Pandemonium broke out – people screaming and jumping into the river, others tightly holding on to their children, and some were climbing over the deck railing to the side of the ship which had risen out of the water. Those below were grabbing onto whatever they could to keep their heads above the water. A few managed to slip out of 18” port-holes resting above the water. Eventually grasps gave way and many were lost in the depths of the ship decks before divers and welders could save them. Bystanders were tossing items into the river hoping these would keep someone afloat. Individuals were diving in the river to rescue as many as possible.

In the end 844 people perished including 22 entire families. Temporary morgues were setup and the task of identifying loved ones was overwhelming. Spouses were lost, children became orphans, and parents cried over the loss of their children. Some families rejoiced in the safe return of loved ones while mourning the loss of other family members. Many families lost their only source of income. The capsizing of the S.S. Eastland marked the greatest loss of life in Chicago or the Great Lakes.

Chicago jumped into action to help from rescue efforts to raising funds. Within two weeks $350,000 was raised for the relief of those families in need. Businesses helped in many ways, for instance Marshall Fields sent blankets to cover the victims and warm those pulled from the river. Storefronts and hotels opened their doors as shelters and medical stations. Phone lines were installed and lists of victims and survivors were complied and forwarded to the switch board operators at the plant in Cicero.

Western Electric provided compensation to the families by establishing two funds. One was to help with the funeral expenses including cemetery plots and even a new suit if necessary. The other provided funds for food and everyday expenditures. The company gave needed medical care and inoculated over 200 people against typhoid, and adopted a policy of favoring victims’ relatives in application for employment.

Czech, Polish, German, Italian, and Swedish immigrants were among the nationalities employed at the Western Electric plant in Cicero. Individual ethnic groups responded and offered assistance. Organizations such as the Masons and Order of the Eastern Star aided with the financial burden of burying the victims as well as supporting and comforting families. An Eastern Star member attended numerous funerals and wrote, “It rained all week at all burials. It seemed as if the heaven was weeping too.”

Newspapers across the country reported on this horrific incident with some sensationalism, such as 1,200 people dead, or 300 still missing. Nonetheless, newspapers were the best source of information and quickly the number of victims was reduced. Everyone wanted to know the cause of the disaster. Fault was wide spread and contributed to improper construction of the steamer, faulty equipment, negligence of the captain and engineer, graft and greed. Naturally, those involved cast the blame on to others. Testimonies were heard and recorded; insurance coverage was certainly not adequate so the families of the victims had to shoulder another burden. The possible causes leading to the S. S. Eastland rolling on its side have been defined yet still disputed. Some like to say she was simply a “cranky ship” and never should have sailed. Testimony proved she sailed for twelve years without incident if the water ballasts contained water. Who was responsible for the water ballasts and keeping the ship even keel is also debated. Trying to find the answer to why the S. S. Eastland capsized was never resolved. Even after almost twenty years of criminal and civil investigation no one was held responsible.

Regardless of the cause, the story of the Eastland Disaster should focus on the people who perished and their families, those who rescued so many survivors, and the businesses and organizations that offered assistance that fateful day. It truly is a story of a community coming together to pay respect to the victims and help the survivors.