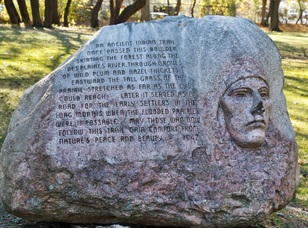

Indian Trail Marker located in section 27

Indian Trail Marker located in section 27

This area was once the burial grounds of the Native Americans of the Potawatomi tribe, and the high ground of this cemetery was once a Native American trail running along the DesPlaines River. Originally two cemeteries, the German Waldheim cemetery was incorporated in 1873, and Forest Home cemetery was incorporated in 1876. With the building of the Chicago and Northwestern Railroad and the Aurora, Elgin and Chicago Railroad the area became accessible as a cemetery for thousands of immigrants living in Chicago whose deceased were not welcome in Chicago cemeteries. With the building of a streetcar line on DesPlaines Avenue, each Saturday and Sunday thousands of people could come out to the cemetery by train, transfer to streetcar and buy flowers to place on the graves of their loved ones.

Over 2,500 graves had to be moved from German Waldheim when the Eisenhower Expressway was built in the 1950‘s. The law required permission of all known descendants who were notified by registered letter or public notice in the newspaper. This delayed completion of this part of the Eisenhower for several years. In 1969 the two cemeteries officially merged, and it was named Forest Home, which is the English translation of the German word Waldheim.

Over 2,500 graves had to be moved from German Waldheim when the Eisenhower Expressway was built in the 1950‘s. The law required permission of all known descendants who were notified by registered letter or public notice in the newspaper. This delayed completion of this part of the Eisenhower for several years. In 1969 the two cemeteries officially merged, and it was named Forest Home, which is the English translation of the German word Waldheim.

Early Days, 1830–1876

The federal government first offered land in northern Illinois for public sale in the 1830s, after the Potawatomi Indians were forcibly removed to west of the Mississippi River under the terms of the 1833 Treaty of Chicago, which ended the Black Hawk War. A French-Indian trapper, Leon Bourassa, purchased acreage in what is now Forest Home Cemetery. According to local legend, Bourassa and his Potawatomi wife, Margaret, claimed this land in part because she wished to remain near the graves of her ancestors. Later accounts also show that Indians occasionally returned to visit the burial mounds well into the Civil War era.

Soon after arriving from Prussia, Ferdinand Haase, an early settler of what is now Forest Park, purchased some of the land formerly owned by Bourassa. Haase built a manor home and began to raise cattle and crops. His only close neighbors were his in-laws, the Zimmermans. Carl Zimmerman, his brother-in-law, died in 1854 and was buried on the property; he was the first non-Indian buried on the land that became Forest Home Cemetery.

The picturesque setting of Haase’s land prompted some of his German friends to encourage him to open a picnic grounds. In 1856, Haase’s Park became a new diversion for Chicago residents, especially those of German descent. An 1860s poster tells the story:

The most beautiful pleasure grounds in the vicinity of Chicago is Haase’s Park… Parties will find various kinds of amusement, as Fishing, Bowling Alley, Hunting, Swinging, Boat Riding.

To make it easier for people to reach his picnic grounds, Haase struck a deal with the Galena & Chicago Union Railroad (later the Chicago and North Western). In exchange for carloads of gravel needed for construction, the railroad built a spur line from the main tracks to Haase’s Park. Through the years, such gravel removal destroyed most of the original glacial ridge, leveled much of the land, and uncovered several burial mounds.

By 1863 Haase began looking beyond the popular recreational use of his land. Increasingly rowdy crowds drew criticism from his neighbors, so that he had to build a jail on the site. He considered subdividing the land for homesites, but found no market at the time.

Another use was proposed for Haase’s land in the late 1860s: as a burial ground for the burgeoning population of Chicago. The old Chicago City Cemetery, located in what is now Lincoln Park, was closed in 1866 as the result of a lawsuit. Difficulties arising from the removal of bodies and monuments were horrendous. By 1869, the Chicago Common Council ordered a ban on future cemeteries in the city; at the time, Graceland and Rosehill Cemeteries to the north and Oak Woods Cemetery to the south were outside the city limits.

Haase’s property was accessible by train and had good drainage; the land would make an ideal cemetery. Gradually, Haase began to sell his land. Along Madison Street to the north, German Lutherans established Concordia Cemetery in 1872, and the northeast corner of today’s Forest Home Cemetery was purchased by a group of German fraternal lodges which established German Waldheim Cemetery in 1873 (Sections in this area are generally identified by letters of the alphabet). According to Bernhard Ludwig Roos, the first superintendent of Waldheim, they took this step because Concordia Cemetery would not permit lodge insignias to be placed on cemetery markers. "Over this intolerance…[they] founded a cemetery where everyone could repose after his own fashion." This Waldheim, or "forest home," was advertised as the only German, non-denominational cemetery in the Chicago area.

At about the same time, some leading landowners and community builders of the Oak Park settlement to the northeast approached Haase with a proposal to create a non-sectarian cemetery on his land that would appeal to the English-speaking, middle- and upper-class citizens of the area. Haase agreed and Forest Home Cemetery was established in 1876 (Sections in this area are designated by the numbers 1–76).

The Importance of Design

Before Forest Home opened, Haase and several other community leaders, including Henry W. Austin, Sr. and James Scoville, traveled to Cincinnati, Ohio, to view Spring Grove Cemetery. This burial ground was considered an outstanding example of cemetery design, and was based in part on the world-famous Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts. But instead of the picturesque "natural" or "rural" look of Mount Auburn, Spring Grove modeled a more park-like, manicured setting for burials, later called the landscape-lawn style. Both presented a stark contrast to European and early American cemeteries.

The landscaping at Forest Home and German Waldheim Cemeteries was meant to lift the spirits of the living. It incorporated curving roads, plantings of trees and shrubbery, and ponds and other water elements. Picnics and boisterous conduct were banned; regulations on monument design and construction ensured a setting that confirmed shared societal values of good order. Even today, the essence of the built environment from the cemeteries’ early decades remains intact, though some features, such as the artificial ponds and grand entrance gates, are gone.

In the 1920s the "memorial park" trend, epitomized by Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale, California, had a significant impact on cemeteries nationwide. This look emphasized the lawn and the use of flat markers rather than monuments; inspirational sculpture gave identity to sections. These design characteristics can be seen west of the river, along the north and west boundaries of the cemetery, in sections which were opened after 1924.

The federal government first offered land in northern Illinois for public sale in the 1830s, after the Potawatomi Indians were forcibly removed to west of the Mississippi River under the terms of the 1833 Treaty of Chicago, which ended the Black Hawk War. A French-Indian trapper, Leon Bourassa, purchased acreage in what is now Forest Home Cemetery. According to local legend, Bourassa and his Potawatomi wife, Margaret, claimed this land in part because she wished to remain near the graves of her ancestors. Later accounts also show that Indians occasionally returned to visit the burial mounds well into the Civil War era.

Soon after arriving from Prussia, Ferdinand Haase, an early settler of what is now Forest Park, purchased some of the land formerly owned by Bourassa. Haase built a manor home and began to raise cattle and crops. His only close neighbors were his in-laws, the Zimmermans. Carl Zimmerman, his brother-in-law, died in 1854 and was buried on the property; he was the first non-Indian buried on the land that became Forest Home Cemetery.

The picturesque setting of Haase’s land prompted some of his German friends to encourage him to open a picnic grounds. In 1856, Haase’s Park became a new diversion for Chicago residents, especially those of German descent. An 1860s poster tells the story:

The most beautiful pleasure grounds in the vicinity of Chicago is Haase’s Park… Parties will find various kinds of amusement, as Fishing, Bowling Alley, Hunting, Swinging, Boat Riding.

To make it easier for people to reach his picnic grounds, Haase struck a deal with the Galena & Chicago Union Railroad (later the Chicago and North Western). In exchange for carloads of gravel needed for construction, the railroad built a spur line from the main tracks to Haase’s Park. Through the years, such gravel removal destroyed most of the original glacial ridge, leveled much of the land, and uncovered several burial mounds.

By 1863 Haase began looking beyond the popular recreational use of his land. Increasingly rowdy crowds drew criticism from his neighbors, so that he had to build a jail on the site. He considered subdividing the land for homesites, but found no market at the time.

Another use was proposed for Haase’s land in the late 1860s: as a burial ground for the burgeoning population of Chicago. The old Chicago City Cemetery, located in what is now Lincoln Park, was closed in 1866 as the result of a lawsuit. Difficulties arising from the removal of bodies and monuments were horrendous. By 1869, the Chicago Common Council ordered a ban on future cemeteries in the city; at the time, Graceland and Rosehill Cemeteries to the north and Oak Woods Cemetery to the south were outside the city limits.

Haase’s property was accessible by train and had good drainage; the land would make an ideal cemetery. Gradually, Haase began to sell his land. Along Madison Street to the north, German Lutherans established Concordia Cemetery in 1872, and the northeast corner of today’s Forest Home Cemetery was purchased by a group of German fraternal lodges which established German Waldheim Cemetery in 1873 (Sections in this area are generally identified by letters of the alphabet). According to Bernhard Ludwig Roos, the first superintendent of Waldheim, they took this step because Concordia Cemetery would not permit lodge insignias to be placed on cemetery markers. "Over this intolerance…[they] founded a cemetery where everyone could repose after his own fashion." This Waldheim, or "forest home," was advertised as the only German, non-denominational cemetery in the Chicago area.

At about the same time, some leading landowners and community builders of the Oak Park settlement to the northeast approached Haase with a proposal to create a non-sectarian cemetery on his land that would appeal to the English-speaking, middle- and upper-class citizens of the area. Haase agreed and Forest Home Cemetery was established in 1876 (Sections in this area are designated by the numbers 1–76).

The Importance of Design

Before Forest Home opened, Haase and several other community leaders, including Henry W. Austin, Sr. and James Scoville, traveled to Cincinnati, Ohio, to view Spring Grove Cemetery. This burial ground was considered an outstanding example of cemetery design, and was based in part on the world-famous Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts. But instead of the picturesque "natural" or "rural" look of Mount Auburn, Spring Grove modeled a more park-like, manicured setting for burials, later called the landscape-lawn style. Both presented a stark contrast to European and early American cemeteries.

The landscaping at Forest Home and German Waldheim Cemeteries was meant to lift the spirits of the living. It incorporated curving roads, plantings of trees and shrubbery, and ponds and other water elements. Picnics and boisterous conduct were banned; regulations on monument design and construction ensured a setting that confirmed shared societal values of good order. Even today, the essence of the built environment from the cemeteries’ early decades remains intact, though some features, such as the artificial ponds and grand entrance gates, are gone.

In the 1920s the "memorial park" trend, epitomized by Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale, California, had a significant impact on cemeteries nationwide. This look emphasized the lawn and the use of flat markers rather than monuments; inspirational sculpture gave identity to sections. These design characteristics can be seen west of the river, along the north and west boundaries of the cemetery, in sections which were opened after 1924.

A Resting Place for All

A review of the interment records for Forest Home and German Waldheim Cemeteries reveals a wide range of ethnic surnames and addresses from Chicago and the near west suburbs. The non-sectarian policies of the cemeteries, their location, their non-denominational nature, and the significant number of fraternal and union plots made these cemeteries the burial place of choice for a wide range of individuals, from evangelist Billy Sunday to anarchist Emma Goldman.

For example, the labor activists executed for their alleged role in the 1886 Haymarket Square bombing are buried here; their striking grave monument has become a magnet for labor leaders, activists, and anarchists from around the world. The monument, designed by Albert Weinert and dedicated in 1893, was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1997.

Victims of epidemics and other disasters also found rest here. Interment ledgers record many deaths from smallpox outbreaks in the 1870s and 1880s, the Iroquois Theatre fire of 1903, the Eastland ship disaster of 1915, and the influenza epidemic of 1918–1919.

The important role played by public transportation in the success of Haase’s Park was also key to the later prosperity of Forest Home and German Waldheim Cemeteries. After 1900, special funeral cars added to streetcars and trains made it convenient for funeral parties to travel with the deceased to the cemetery.

Automobiles also had a significant impact, both directly as a popular means of transportation for funeral parties, and indirectly with the growth of highway systems. When the Eisenhower Expressway (I-290) was built in the 1950s, it cut through the northernmost part of Forest Home, resulting in the movement of several hundred graves.The Cemetery Today

In 1968, major changes came to the cemeteries when the Haase family sold Forest Home to a Chicago real estate developer. The cemetery was merged with the adjacent German Waldheim Cemetery, land along the property’s borders was sold, and some original features, including the grand entrance gates and greenhouses, were removed. The entrance to the original Forest Home Cemetery was closed; the original entrance to Waldheim Cemetery to the north, minus its grand gate, became the entry for the expanded Forest Home Cemetery.

Because of its unique history, this burial ground allows visitors to experience more than just the rich and famous. Local pioneers, including the Austins, Steeles, and Hemingways, share resting space with labor activists and fraternal groups. Noted architects, Civil War generals, a doyenne of modern dance, and a radical anarchist lie with immigrants, children, milliners, and undertakers. Those interred here create a community as diverse, colorful, and interesting as any in the living world.

an excerpt from the Oak Park Historical Society’s award-winning book, Nature’s Choicest Spot: A Guide to Forest Home and German Waldheim Cemeteries

A review of the interment records for Forest Home and German Waldheim Cemeteries reveals a wide range of ethnic surnames and addresses from Chicago and the near west suburbs. The non-sectarian policies of the cemeteries, their location, their non-denominational nature, and the significant number of fraternal and union plots made these cemeteries the burial place of choice for a wide range of individuals, from evangelist Billy Sunday to anarchist Emma Goldman.

For example, the labor activists executed for their alleged role in the 1886 Haymarket Square bombing are buried here; their striking grave monument has become a magnet for labor leaders, activists, and anarchists from around the world. The monument, designed by Albert Weinert and dedicated in 1893, was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1997.

Victims of epidemics and other disasters also found rest here. Interment ledgers record many deaths from smallpox outbreaks in the 1870s and 1880s, the Iroquois Theatre fire of 1903, the Eastland ship disaster of 1915, and the influenza epidemic of 1918–1919.

The important role played by public transportation in the success of Haase’s Park was also key to the later prosperity of Forest Home and German Waldheim Cemeteries. After 1900, special funeral cars added to streetcars and trains made it convenient for funeral parties to travel with the deceased to the cemetery.

Automobiles also had a significant impact, both directly as a popular means of transportation for funeral parties, and indirectly with the growth of highway systems. When the Eisenhower Expressway (I-290) was built in the 1950s, it cut through the northernmost part of Forest Home, resulting in the movement of several hundred graves.The Cemetery Today

In 1968, major changes came to the cemeteries when the Haase family sold Forest Home to a Chicago real estate developer. The cemetery was merged with the adjacent German Waldheim Cemetery, land along the property’s borders was sold, and some original features, including the grand entrance gates and greenhouses, were removed. The entrance to the original Forest Home Cemetery was closed; the original entrance to Waldheim Cemetery to the north, minus its grand gate, became the entry for the expanded Forest Home Cemetery.

Because of its unique history, this burial ground allows visitors to experience more than just the rich and famous. Local pioneers, including the Austins, Steeles, and Hemingways, share resting space with labor activists and fraternal groups. Noted architects, Civil War generals, a doyenne of modern dance, and a radical anarchist lie with immigrants, children, milliners, and undertakers. Those interred here create a community as diverse, colorful, and interesting as any in the living world.

an excerpt from the Oak Park Historical Society’s award-winning book, Nature’s Choicest Spot: A Guide to Forest Home and German Waldheim Cemeteries